Calvin looks older here, but in the dream, he was about six or seven years old.

His teacher caught him and set him at a bunch of other activities with the other kids. Calvin had a fun day and was excited about the school sleepover.

But when it was time to sleep, and the other kids had all climbed into their beds, on either side of the teacher's big bed, Calvin felt a panic. So he climbed into the teacher's bed, which woke her. She was angry about it, but when she saw that he was crying, she said, "Don't worry, Calvin, there is something you can do." And she pointed at something off-panel; in my mind, it was a book.

I was adjusting photographs for uploading, and one photo of some kind of evergreen caught my eye. It wasn't a pine — the bark was different — but it had needles. I had planned to crop the photo around the tree, with the house — my house, but not in Kalsangi; someplace between the edges of "Christina's World" and the edge of a forest, of which the evergreen was one tree to say, "You are near a forest" — in the background. But as I zoomed in on the photo, I was drawn closer and closer to the tree, until it filled my screen. The bark was gray-green and had lichens, and the needle-leaves looked feathery, like frost patterns on glass, and almost soft. I saw that no matter how close I zoomed in on the trunk and the leaves, I could still make out the shadow of the house behind them.

There was a man, David. He was not Calvin, but he was like Calvin. I was him, and I also watched him, the way you can in dreams. No more panels here.

In his house, David played with his children, two sons and a melancholy daughter — his youngest. And then his children were gone, and David in his dark brown suit with a white shirt went from his son's room, crossed a sort of red hall with a checkerboard floor and some arches in the walls, and went into his daughter's rom. He was sorry he hadn't spent enough time with them.

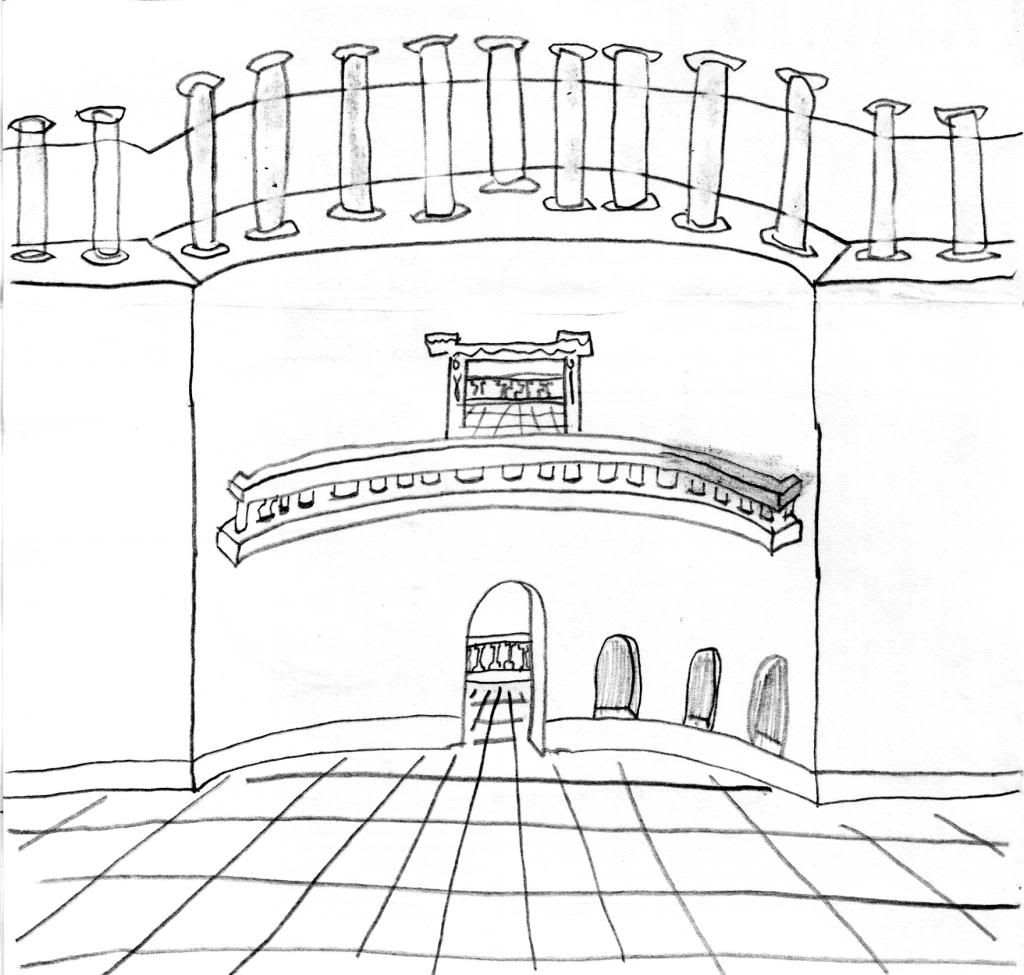

The hall in David's house. The pillars at the top are supporting a black or dark brown roof; the space between the pillars is open for air to come in.

Both the children's rooms were a mess. The daughter's room was all papers and paints and books, scattered all over the place. She was collecting these books by a guy whose last name was Funk (first name Paul?). His style was Shaun Tan meets M.C. Escher. One book she didn't have yet — there was a long list, and she had only one or two — was titled, "Imelda's House."

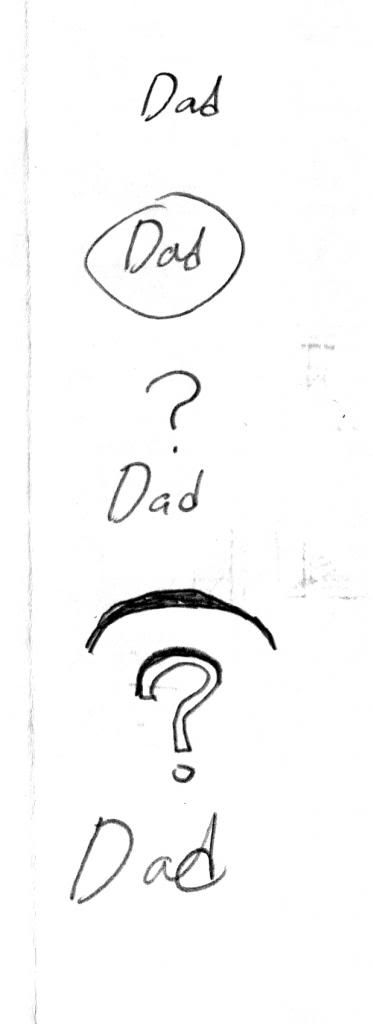

David found a diary where his daughter had scribbled things about him. (David talked aloud.) On one page, the word "Dad" changed before our eyes:

and David realized that his daughter had learned something about him.

On the opposite page, the left-hand page, some pencil writing about her dad had been erased and then covered by other pencil writing about her dad. David erased this, and the old writing reappeared, and he saw that his name was not David [Lastname] but David Davies. Davies was underlined three times.

And then David was in another town, in its tiny, Shaker-style, dimly lit records hall. Afternoon sunlight came in from outside through high slats. He was holding the same book his mother must have held years before — the one that said her name was actually Gwendolyn G[...] and not Gwendolyn [Lastname]. And he was in despair, in a kind of panic, because how many books were there left to go through, and when would he finally find out who he really was?

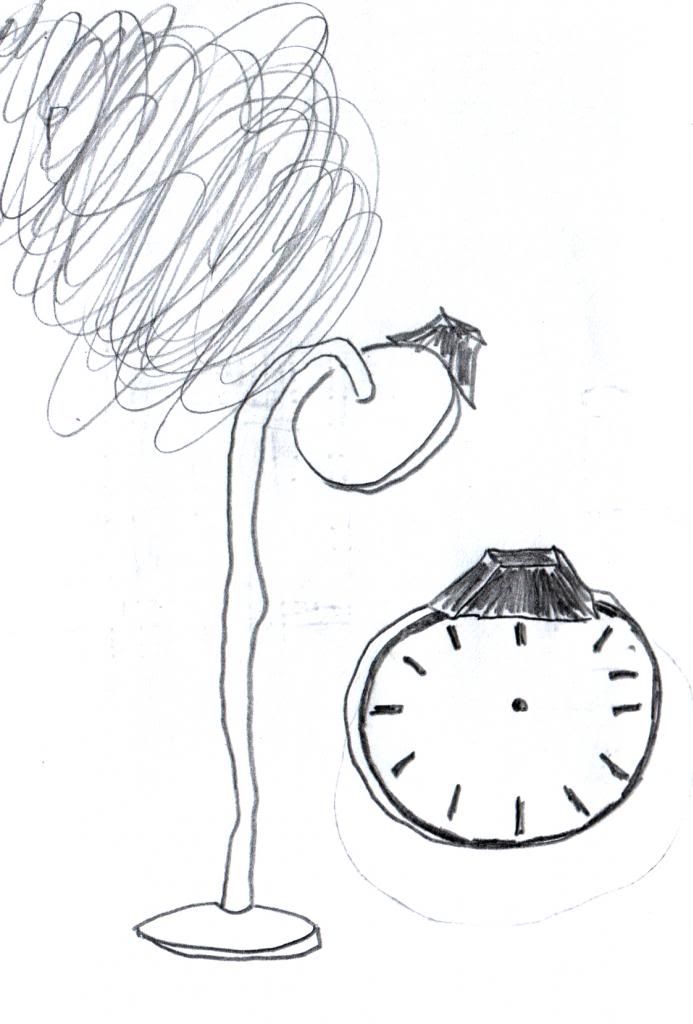

David went into the next room, the hall in his home, faded red with the checkerboard floor. As he cried, a great clock came down from the ceiling. Its circular face was white, and it had the peaked square top of a lantern. Its body was thin and silver, like a tall designer lamp's, and the clock face bobbed gently at the end of it. The silver shone yet was not smoothed down; it was as if someone had stretched that metal out by hand and then left it like that, covered with the impressions of the insides of his fists.

Above the clock, there was a swirling, tornado-like vortex and some thunder and lightning. The clock said to David to not be afraid; he could find the answers if he sought them.

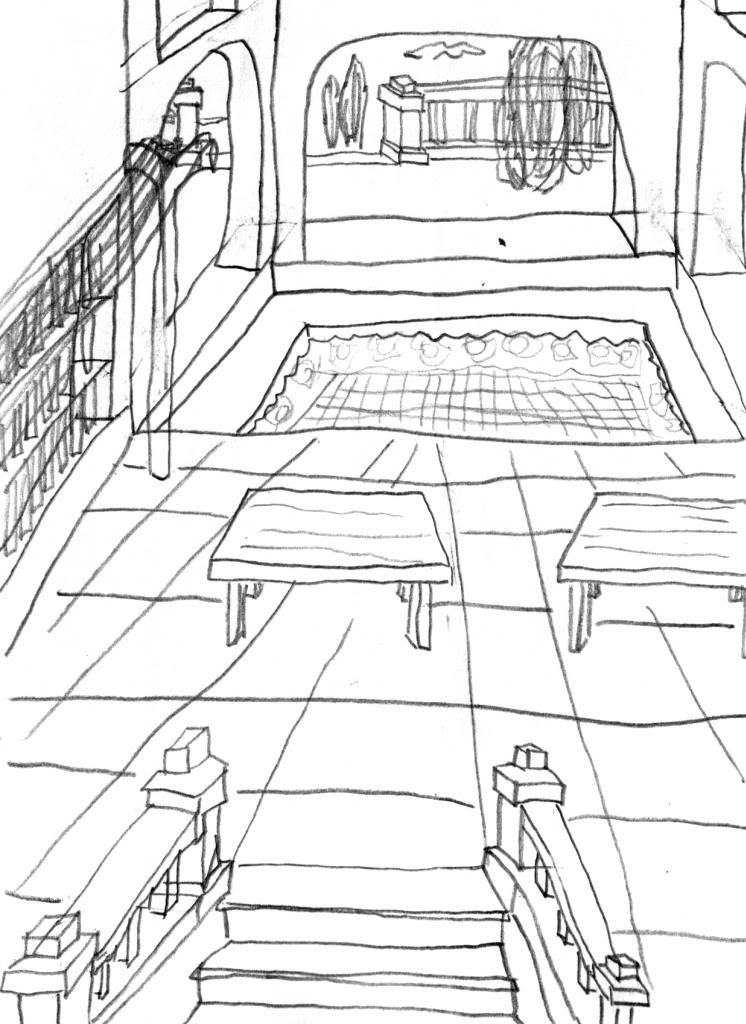

David went up with the clock into the vortex, and then they were in a great library. It was a messy library; the shelves were out of order, and there were books scattered on the floor. The room David and the clock had entered was rectangular and had three walls, all lined with bookshelves from floor to ceiling, plus balconies. The two long walls had doorways to other rooms. The center of the room had a wooden staircase that dropped down to more rooms. Past the staircase were reading tables, and past those reading tables, where the fourth wall would have been, was a view that looked a lot like Escher's "Gallery" or "Other World", but with blue and green gardens instead of outer space beyond the arches.

There were other people in the library. They scrambled frantically from shelf to shelf, grabbing books, poring through the pages, filling their arms, and looking for their answers. Men, women, and children, young people, old people — all kinds of people rushed this way and that with their stacks. David quickly joined them, and suddenly, I was outside David. I wasn't on a quest like him and the others; I was just a visitor. I looked at an old man with a long white beard at one of the reading tables, and I wondered how long any of these people would be here, knowing that there could be any number of rooms and staircases and books.

The room was faded red, with a checkerboard floor. In front of the shelves were decorative white metal trellises. I approached one of the shelves on the opposite wall. I saw that all the books were fictional, and there were volumes and volumes and series and series by so many different authors from so many thousands of years. I saw two series, one red and one green, but both with a picture of a man in a Martin Luther getup on the cover. I wondered how long it would take someone to piece together all the clues in all these books and what sort of answer they'd get in the end.

One of the books I saw.

I saw a shelf full of those books by Funk, that author David's daughter had liked, and since I had liked the illustrations, I decided that I'd read the books. I wonder if there was anyone else there who was just reading for fun and not looking for answers. I reached for Funk book No. 1 and saw that the first illustration was of a place like this library, with a checkerboard floor, people looking at shelves and books, and an arched garden in the background. Among the people in the illustration, there was a man who looked like David and a girl in a red dress that I had seen when we'd entered the library.

I tried to read the first paragraph and immediately found it difficult, the way you sometimes read the same paragraph several times over without anything in it sinking in.

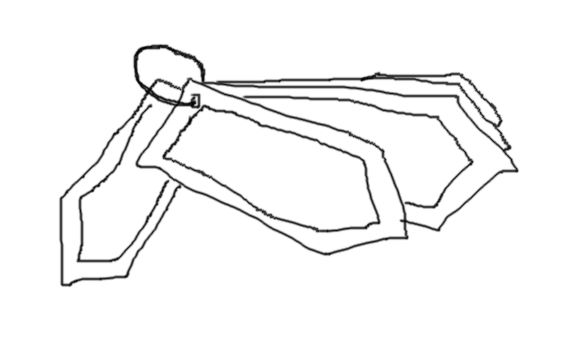

So, I showed the book to the clock, which was going around with a ring-bound book shaped like a red ribbon or arrow. The clock was putting the shelves back in order. I asked it, "Why can't I read this book?" And it took the book from me and flipped through the pages of its red book — which was strange, because the clock didn't have hands, except for the clock hands on its face, and I can't even remember what time it showed. After finding the right page, the clock said, "Today is September. It is not the time for F. You'll have to try another time. Here, try [...]." And he left me by another shelf to put the Funk book back where I'd found it.

The clock's "book". I'd forgotten to draw it, so I made this drawing in GIMP. Now that I think about it, the pages look like the hands of a clock.

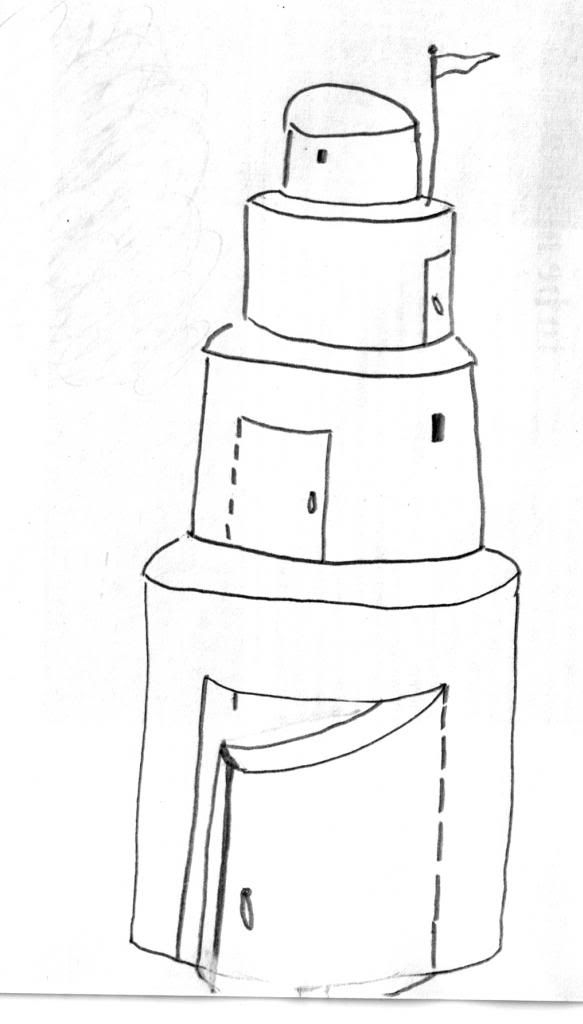

On that shelf, I saw another Funk book, possibly misplaced. It wasn't like a regular book, but when I saw it, the word that came to mind was "book". It was called "Imelda's House." It was shaped like a cake tower, like something out of a Giorgio de Chirico painting, and instead of pages or a cover, it had little doors in the sides that you could open, to see dioramas of things inside the building. I don't remember any of the scenes I saw except the one behind the biggest door: a library with decorative white trellises in front of the shelves, faded red walls, and a checkerboard floor, and with the clock standing over a pile of books on the floor and with the gray cotton vortex above its head.

"Imelda's House," by Paul(?) Funk

After this, I woke up.

--

I guess I should lay off the surrealists for a while.

No comments:

Post a Comment