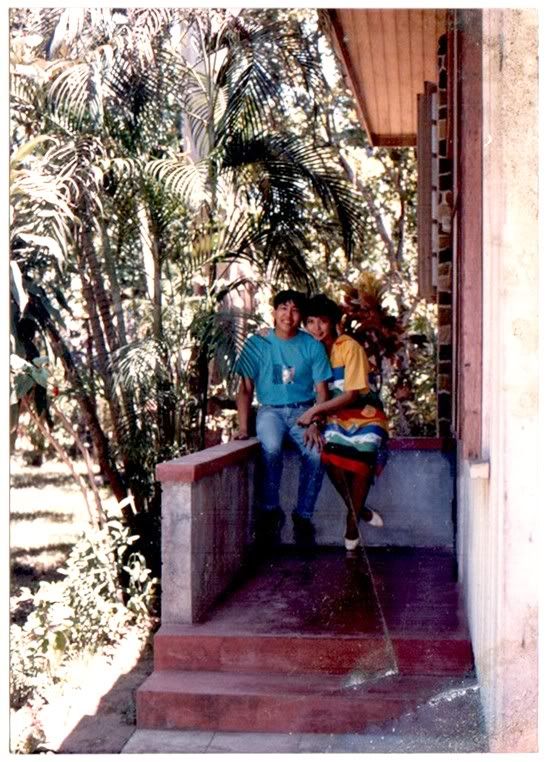

The morning of my parents' anniversary last week, I was scanning some of my paternal grandmother's old photos. Among the albums, I found this photo of Mom and Dad outside my maternal grandparents' house in Dumaguete. On the back of the photo, my lola's loopy cursive let me know that this was taken in April 1987, just two months before my parents' first wedding anniversary and about halfway through Mom's pregnancy with me.

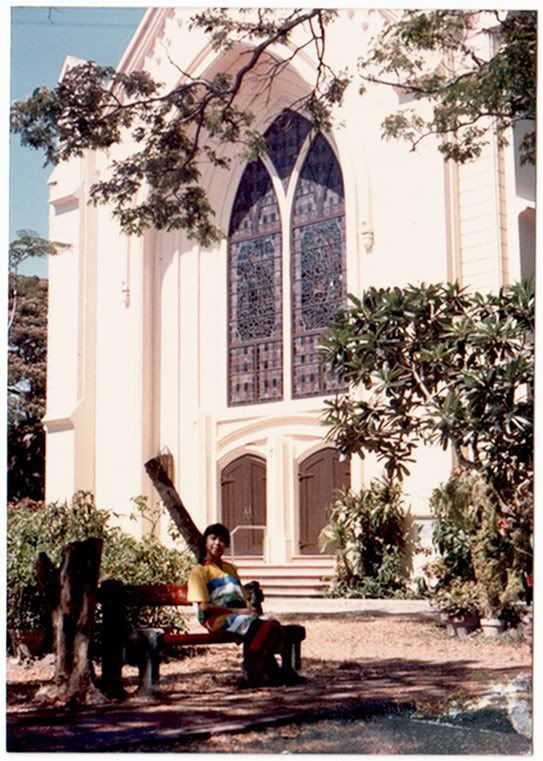

There was also this photo of her sitting in the shade outside Silliman Church. I think her belly is a little more visible here, but then again, it could just be the dress; Mom was pretty skinny until much, much later.

I guess this is the earliest known photo of us together.

People often tell me that I look like my mom in miniature. On more than one occasion, I've stood in front of her old classmates and received a look of both recognition and bewilderment, perhaps as though they're being visited by the Linda of their Silliman days.

Christmas, two years ago.

But, I've always had mixed feelings about the fact that our physical resemblance is pretty much where our similarities end.

Mom likes pop ballads, romantic comedies, shopping (especially for bags and shoes), bright floral prints, Piolo Pascual, Martha Stewart-y things, and keeping up a busy social and civic life.

I like alternative music, action movies and dramas (and cartoons, which are really both), not shopping, subdued colors, not being a big fan of celebrities in general, TheMarySue/Boingboing things, and holing up in my room with a book.

I like who I am and what I like, but I have this weird guilt knowing that my mom had only one daughter, and that daughter wasn't very interested in the things she liked. I sometimes wish my sister had been born, just so my mom could have had a girl who appreciated kikay-ness better.

When I was growing up, my mom and I didn't get along very well. It wasn't just that we had different interests; I also wasn't a very agreeable child.

That's the face of a rebel right there.

I was satisfied with my grades and my relatively high rank, so I resented Mom for nagging me to study more. I had few friends and wasn't interested in making more, so I resented Mom for telling me to go out and join my classmates at parties, where I just sat in a corner and spaced out, wishing I were home with my books.

I grumbled whenever I had to wear makeup for anything, I could never keep my room clean enough for her standards, and I cringed at some of the things she got me to wear to church on Sundays. I guess it's a classic case of mother and daughter butting heads over her telling me what to do, but we just clashed so much over the years that it was hard for me to be grateful for the things she "got right."

For instance, she picked most of my Christmas gifts "from Mom and Dad" over the years, and some of the books she got me are still favorites today. She was there when we got every pair of sneakers I've ever liked, including the ones I've been wearing for the past two years. In fact, every birthday and Christmas gift she's gotten me, though I may not have liked every one, was clearly chosen with love.

She also baked me a chocolate cake from scratch for one particularly special birthday. Today, I can no longer remember why I thought it was a special birthday, but I still remember the fact that she made me that delicious cake.

When I ended up being the only girl without a date to the junior prom, I think she was partly responsible for finding me one among Gensan's rich sons. That prom night was horrible, but, looking back now, I appreciated her help.

She also helped plan my sweet 16, which was one traditionally girly thing that I wanted because going away to college meant I wouldn't be home for a debut. When I did turn 18, she flew to Manila to spend that birthday with me, even if it was a weekday and I had an accounting exam the next day.

Compared with a lot of moms, she was actually pretty liberal with me. She let me cover one wall of my room with all my teenage ranting. When I asked her in one of our bigger fights to just leave me alone, she actually did for a few months. She let my first boyfriend come over all the time, and she didn't set me a curfew on that last night I saw him, before I left for Manila.

I know from schoolmates that parents have ways of trying to control their children even from far away, so even the fact that I've been independent for the past couple of years is sort of her and Dad's doing (or not-doing) as well as mine.

She's also there for me whenever I do want to hear her opinion, even if only through emails and phone calls. She was the one to tell me that that first boyfriend was cheating on me. She's shared stories of her own college years and 20s, and those stories have helped me feel both more normal and more unique, if that makes any sense.

So really, I'm disappointed in myself because until now, my knee-jerk reaction whenever she suggests something is to be cranky and defensive. My answers to, "You should get this dress," "Why don't you put the cabinet over there?" and even, "You should pick out a good table [which I will pay for] for your new apartment," are unnecessarily terse. Somewhere deep down, there's a 15-year-old girl who still thinks, "Mom doesn't understand me," or, "Mom doesn't know what I like."

Too late, I remind myself, "Mom loves me," "Mom wants to bond with me," and, "Mom just wants to make sure I'm okay," — and that sometimes, "okay" just means I have a rice cooker, some nice kitchen towels, and a good boyfriend who may or may not look like Piolo Pascual.

I love you, Mom. I'm really glad I'm your daughter, too.